In a landmark decision, the German Constitutional Court has ruled that mass surveillance of telecommunications outside of Germany conducted on foreign nationals is unconstitutional. Thanks to the chief legal counsel, Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte (GFF), this a major victory for global civil liberties, but especially those that live and work in Europe. Many will now be protected after lackluster 2016 surveillance reforms continued to authorize the surveillance on EU states and institutions for the purpose of “foreign policy and security,” and permitted the BND to collaborate with the NSA.

In its press release about the decision, the court found that the privacy rights of the German constitution also protects foreigners in other countries and that the German intelligence agency, Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), had no authority to conduct telecommunications surveillance on them:

“The Court held that under Art. 1(3) GG German state authority is bound by the fundamental rights of the Basic Law not only within the German territory. At least Art. 10(1) and Art. 5(1) second sentence GG, which afford protection against telecommunications surveillance as rights against state interference, also protect foreigners in other countries. This applies irrespective of whether surveillance is conducted from within Germany or from abroad. As the legislator assumed that fundamental rights were not applicable in this matter, the legal requirements arising from these fundamental rights were not satisfied, neither formally nor substantively.”

The court also decided that as currently structured, there was no way for the BND to restrict the type of data collected and who it was being collected from. Unrestricted mass surveillance posed a particular threat to the rights and safety of lawyers, journalists and their sources and clients:

“In particular, the surveillance is not restricted to sufficiently specific purposes and thereby structured in a way that allows for oversight and control; various safeguards are lacking as well, for example with respect to the protection of journalists or lawyers. Regarding the transfer of data, the shortcomings include the lack of a limitation to sufficiently weighty legal interests and of sufficient thresholds as requirements for data transfers. Accordingly, the provisions governing cooperation with foreign intelligence services do not contain sufficient restrictions or safeguards. The powers under review also lack an extensive independent oversight regime. Such a regime must be designed as continual legal oversight that allows for comprehensive oversight and control of the surveillance process.”

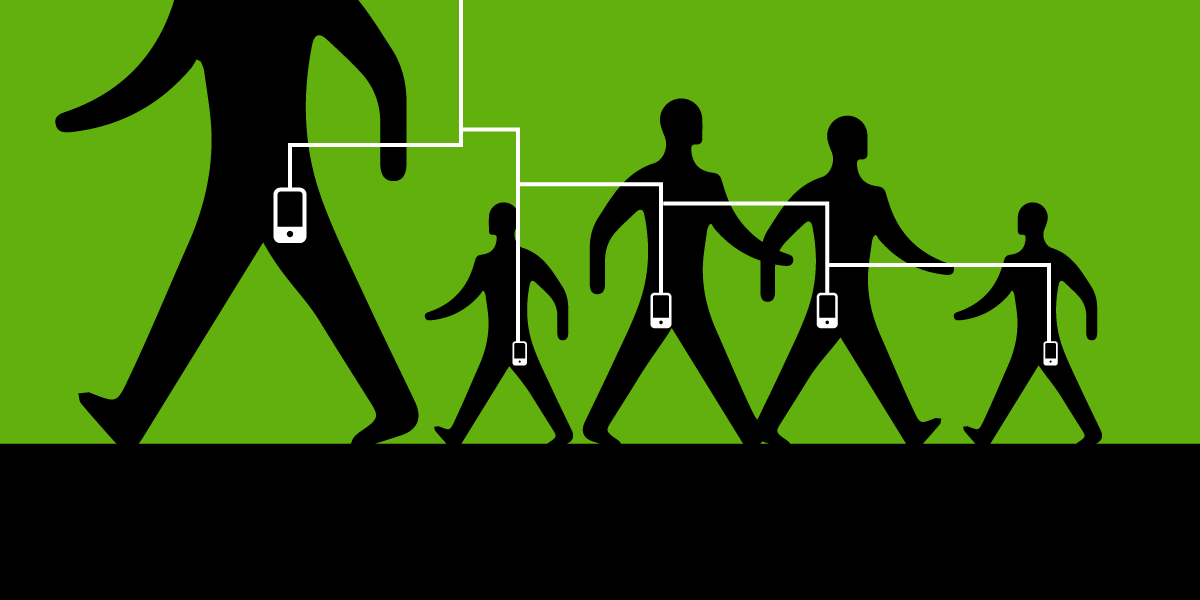

The hearing comes after a coalition of media and activist organizations including the Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte filed a constitutional complaint against the BND for its dragnet collection and storage of telecommunications data. One of the leading arguments against massive data collection by the foreign intelligence service is the fear that sensitive communications between sources and journalists may be swept up and made accessible by the government. Surveillance which, purposefully or inadvertently, sweeps up the messages of journalists jeopardizes the integrity and health of a free and functioning press, and could chill the willingness of sources or whistleblowers to expose corruption or wrongdoing in the country. In September 2019, based on similar concerns about the surveillance of journalists, South Africa’s High Court issued a watershed ruling that the country’s laws do not authorize bulk surveillance, in part because there were no special protections to ensure that the communications of lawyers and journalists were not also swept up and stored by the government.

In EFF’s own landmark case against the NSA’s dragnet surveillance program, Jewel v. NSA, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press recently filed an Amicus brief making similar arguments about surveillance in the United States. “When the threat of surveillance reaches these sources,” the brief argues, “there is a real chilling effect on quality reporting and the flow of information to the public.” The NSA is also guilty of carrying out mass surveillance of foreigners abroad in much the same way that the BND was just told it can no longer do.

Victories in Germany and South African may seem like a step in the right direction toward pressuring the United States judicial system to make similar decisions, but state secrecy remains a major hurdle. In the United States, our lawsuit against NSA mass surveillance is being held up by the government argument that it cannot submit into evidence any of the requisite documents necessary to adjudicate the case. In Germany, both the BND Act and its sibling, the G10 Act, as well as their technological underpinnings, are both openly discussed making it easier to confront their legality.

The German government now has until the end of 2021 to amend the BND Act to make it compliant with the court’s ruling.

EFF wishes our hearty congratulations to the lawyers, activists, journalists, and concerned citizens that worked very hard to bring this case before the court. We hope that this victory is just one of many we are—and will be—celebrating as we continue to fight together to dismantle global mass surveillance.

Source: eff.org