Tracking children has never been easier. Nice for parents, not for privacy.

PAUL WALLICH usually walks his small son to the bus stop a stone’s throw from their Vermont home. But he can use a robot too: a football-sized drone, hovering several metres off the ground, follows a beacon stashed in the little boy’s school bag. A smartphone strapped to the device beams back video.

Few parents are as handy as that, but even Luddites like the idea of keeping an electronic eye on the young. An early offering, in 2003, was Wherify, a tracking device which locks to a child’s wrist. Devices invented since then protect autistic children, who easily get lost, or into danger. Youngsters on Canadian farms wear radio tags on bracelets to signal their proximity to adults operating heavy machinery.

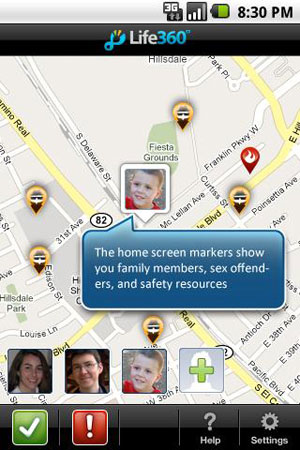

Longer battery life and miniaturisation are making tracking cheaper and more practical. The easiest way is to use smartphones. Many mobile operators offer child-tracking at extra cost, but the number of free tracking applications is growing fast. Life360 rocketed from 1m registered users in 2010 to nearly 26m now. Berg Insight, a research firm, reckons that 70m Americans and Europeans will be tracking family members by 2016.

These services and devices can provide children’s location, or send alerts about their behaviour: when they return home, or stray beyond an agreed boundary, or go out late. Speed detection reveals when somebody is in a vehicle—and whether it is breaking the speed limit.

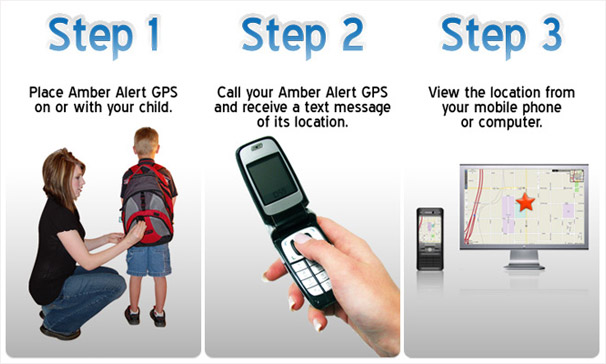

No devices, so far, have full chaperone functions—such as revealing furtive movements in a stationary vehicle. But some providers do have ingenious extra features. The pocket-sized tracking beacons of Amber Alert GPS, a company based in Utah, carry a microphone to let parents eavesdrop. SecuraTrac, a Californian firm, has a product that disables a phone’s e-mail and text functions when it is moving: that stops boy-racers from typing while driving. Life360’s maps highlight the addresses of sex offenders.

Parents in Japan and America are the keenest on such gizmos. Europeans, seemingly more relaxed about child safety and with more complex privacy laws, are less enamoured. Some European countries require minors’ consent for some kinds of surveillance. Child tracking appeals particularly to middle-class families in South American countries who worry about gang crime and kidnapping, says André Malm, an analyst at Berg Insight.

Public authorities are keen, too. Schools in Osaka began issuing radio frequency identification (RFID) tags to students in 2004. Sensors in school buildings read them to check pupils’ attendance and location (though not what they do off the premises). In Dubai the same technology notifies parents when their progeny get on or off school buses. In March last year 20,000 schoolchildren in the Brazilian city of Vitoria da Conquista had radio tags sewn into their uniforms to help detect truants.

In August 2012 two schools in San Antonio, Texas, embedded RFID tags in identity badges belonging to their 4,200 students. These help administrators to count students who turn up to class but miss the morning register. Because funding is linked to daily attendance, the system enables schools to claim more taxpayer cash. On January 8th a court lifted an earlier injunction halting the expulsion of a child who refused to wear the badge on religious grounds (some Christians liken the devices to the Mark of the Beast, foreseen in the Bible). The family intends to appeal.

X marks the child

But what about privacy? Enthusiasts say tracking means more freedom, not less. Parents who know they can easily find their children may be happier to let them roam. Teenagers are spared annoying phone calls. Daisy Ashford, a mother of children aged ten and eight who lives in Ashland, Virginia, says her children like the “James Bond” feel of their Amber Alert trackers. Her military family moves every 18 months, making it hard to develop a protective network of friends and neighbours: the devices are “another set of eyes”.

Critics say tracking does not really protect children. Savvy kidnappers will dispose of phones or other devices (implantable tracking chips are, so far, the stuff of spy movies only). And strangers rarely attack children anyway: parents are the most likely murderers, and accidents are a far graver danger than assault. “Location tracking won’t stop your child falling into a river,” says Anne-Marie Oostveen, who studies surveillance at Oxford University. For fretful parents the new devices may just mean still more grounds for worry.

The same technology also enables snooping on adults. In America mobile subscribers can buy location-tracking services for all users of a family phone plan. Some survivors of domestic violence say this makes it harder to escape. Parents use webcams to keep an eye on their children’s carers (generally legal, though the ethics of hidden cameras are contested, and covertly captured audio can break laws on wiretapping). A Saudi government agency that sends men text messages if their children leave the country also helps track wives.

Others fear that children who submit to tracking in schools will more readily accept state surveillance in adulthood. In August a coalition of American civil-rights outfits advised schools not to make such tracking mandatory. It termed the technology “dehumanising” and said that, where it operates, sensors should be visible.

Small fixes can make tracking by parents more palatable, too. Services that help kids report their location, perhaps by “checking in” as they move around, calm anxious grown-ups with less annoyance for the young. An app called Glympse lets users share their location for a few minutes at a time; WalkMeHome, a Swedish app also available in English, helps people share their whereabouts with trusted contacts any time they feel unsafe. A prototype tracker built by Microsoft substituted detailed location data for broader descriptions (“at school”, “at home” or “at work”). Such humdrum messages may be less fun than child-tracking drones—but they are also less alarming.

Source: economist.com