Amazon is instituting a one-year moratorium on the use of its facial recognition technology by police.

Civil rights groups have long for a moratorium on Rekognition

As a national spotlight remains focused on police brutality, Amazon is implementing a one-year moratorium on the use of its facial recognition technology by police departments.

This marks a significant reversal for Amazon, which, until now, had not been swayed by calls from dozens of organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union not to sell the technology to law enforcement because people of color are disproportionately harmed by police practices. Amazon’s technology, known as Rekognition, they argue, could exacerbate the problem.

‘The most sophisticated, modern technology that exists’

A little over a year ago, for example, Amazon shareholders voted down a proposal that would have restricted the sale of Rekognition to government agencies. (Those shareholders also rejected a proposal to study the extent to which Rekognition may violate civil rights.)

Adweek reached out to Amazon about Rekognition following news from IBM earlier this week in which CEO Arvind Krishna told members of Congress that IBM no longer offers its general purpose facial recognition software because the company opposes its use for surveillance, racial profiling and violations of human rights. Amazon did not respond.

Andrew Jassy, CEO of Amazon Web Services, which oversees Rekognition, has, however, spoken to the PBS documentary series Frontline. In an interview that aired in February, he said Amazon believes police departments should be allowed to experiment with Rekognition because law enforcement should have access to “the most sophisticated, modern technology that exists.”

He noted that Amazon has never received a report of misuse by law enforcement, and he believed any abuse would be made public.

“We see almost everything in the media today, and I think you can’t go a month without seeing some kind of issue that somebody feels like they’ve been unfairly accused of something of some sort, so I have a feeling that if you see police departments abusing facial recognition technology, that will come out … It’s not exactly kept in the dark when people feel like they’ve been accused wrongly,” Jassy told Frontline.

What a difference a few months makes.

Like any burgeoning technology, where, when and how to use facial recognition is a complicated issue.

Facial recognition software has biases

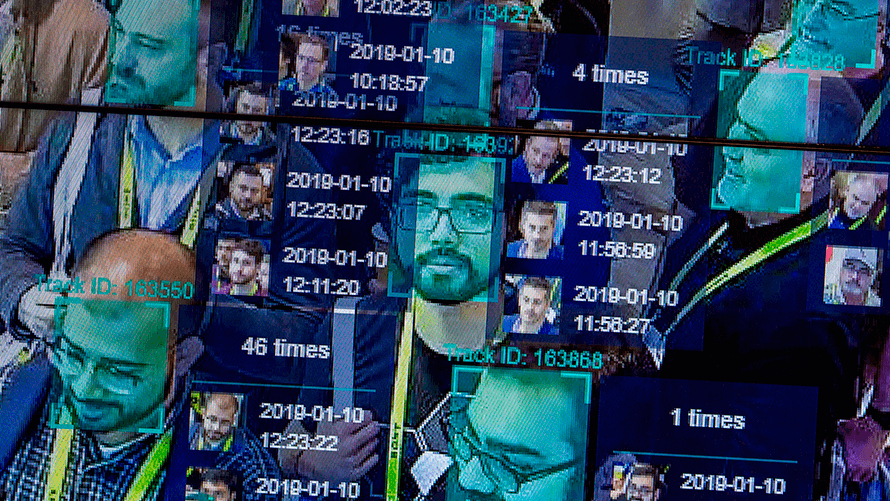

First and foremost, multiple studies have demonstrated the technology is less capable of accurately identifying women and people of color.

In July 2018, for instance, the ACLU released a study in which Rekognition incorrectly matched 28 members of Congress with people in mugshots—and the false matches were disproportionately of people of color. (But it’s hardly the only study.)

At the time, an Amazon spokesperson pointed to uses that benefit society, such as preventing human trafficking and finding missing children, and said the ACLU test could have been improved by using a higher confidence threshold for matches, which is what it recommends for law enforcement. (Jassy repeated these talking points in his Frontline interview.)

The Amazon rep also noted Rekognition is “almost exclusively” used to narrow the field of possible suspects. But that’s not always the case with facial recognition. Look no further than the January investigation by The New York Times that found officers in Pinellas County, Fla.—which, to be clear, were using their own in-house database—sometimes used facial recognition as the basis for arrests when they had no other evidence.

Last February, Amazon said it was planning to work with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the U.S. government lab with an industry benchmark for facial recognition, to develop standardized tests to remove bias and improve accuracy. Until that point, Amazon had not submitted Rekognition for testing alongside 76 other developers because it said its technology was too “sophisticated.”

Sixteen months later, however, a representative for NIST said Amazon still has not submitted an algorithm.

The public may not know police are watching

Another part of the problem is the public doesn’t always know when facial recognition is in use.

The city of Orlando, Fla. (which later dropped the technology) and the Washington County, Ore. Sheriff’s Office are among the few government agencies publicly identified as Amazon customers, but they certainly aren’t alone in using facial-recognition technology from Amazon or elsewhere.

"We’re glad the company is finally recognizing the dangers face recognition poses to Black and Brown communities."

Nicole Ozer, ACLU

A 2016 report from the Center on Privacy and Technology at the Georgetown School of Law found that the LAPD, as well as police departments in Chicago and Dallas, had either bought the technology, expressed an interest in it or were already running real-time facial recognition off of street cameras. (A lawsuit over information related to the NYPD’s use of facial recognition technology is still pending.)

In a January 2019 interview, Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst at the ACLU, explained that law enforcement often purchases facial recognition technology with surveillance grants from the federal government, so it doesn’t have to seek approval for funding for its use on the local level. (He was not available for further comment.)

Governmental oversight is nonexistent

Another big problem is oversight. As in, there is none.

Organizations like the ACLU, The Privacy Center and the Center for Democracy and Technology have called for legislation to regulate the use of facial recognition.

Even Amazon has said governments should “put in place stronger regulations to govern the ethical use of facial recognition technology” and, in its statement Wednesday, said it hopes the “one-year moratorium might give Congress enough time to implement appropriate rules.” (It also told NIST it was still going to participate in the Facial Recognition Vendor Test.)

The ACLU is now calling on lawmakers to add language to the Justice in Policing Act, introduced Monday, that prohibits facial recognition from being used with body cameras.

“It took two years for Amazon to get to this point, but we’re glad the company is finally recognizing the dangers face recognition poses to Black and Brown communities and civil rights more broadly,” said Nicole Ozer, technology and civil liberties director with the ACLU of Northern California.

Ozer also noted “the threat to our civil rights and civil liberties will not disappear in a year,” and called on Amazon to do more—including ending sales of the smart doorbell Ring, which she said “[fuels] the overpolicing of communities of color.”

In 2018, the ACLU flagged a patent filing from Amazon that detailed plans to combine Rekognition and Ring to allow law enforcement to match the faces of passersby with photos of suspicious persons.

Source: adweek.com