Lessons from a year of Covid

How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.

Why, then, has there been so much death and suffering? Because of bad political decisions.

In previous eras, when humans faced a plague such as the Black Death, they had no idea what caused it or how it could be stopped. When the 1918 influenza struck, the best scientists in the world couldn’t identify the deadly virus, many of the countermeasures adopted were useless, and attempts to develop an effective vaccine proved futile.

It was very different with Covid-19. The first alarm bells about a potential new epidemic began sounding at the end of December 2019. By January 10 2020, scientists had not only isolated the responsible virus, but also sequenced its genome and published the information online. Within a few more months it became clear which measures could slow and stop the chains of infection. Within less than a year several effective vaccines were in mass production. In the war between humans and pathogens, never have humans been so powerful.

Moving life online

Alongside the unprecedented achievements of biotechnology, the Covid year has also underlined the power of information technology. In previous eras humanity could seldom stop epidemics because humans couldn’t monitor the chains of infection in real time, and because the economic cost of extended lockdowns was prohibitive. In 1918 you could quarantine people who came down with the dreaded flu, but you couldn’t trace the movements of pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic carriers. And if you ordered the entire population of a country to stay at home for several weeks, it would have resulted in economic ruin, social breakdown and mass starvation.

In contrast, in 2020 digital surveillance made it far easier to monitor and pinpoint the disease vectors, meaning that quarantine could be both more selective and more effective. Even more importantly, automation and the internet made extended lockdowns viable, at least in developed countries. While in some parts of the developing world the human experience was still reminiscent of past plagues, in much of the developed world the digital revolution changed everything.

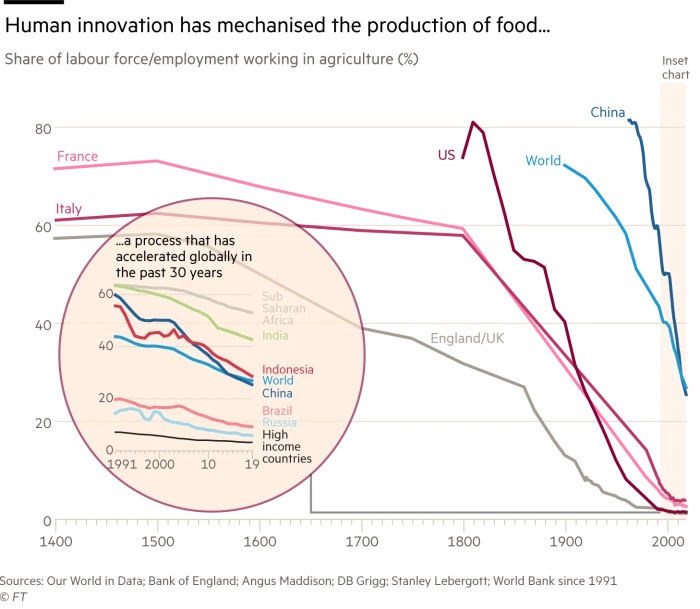

Consider agriculture. For thousands of years food production relied on human labour, and about 90 per cent of people worked in farming. Today in developed countries this is no longer the case. In the US, only about 1.5 per cent of people work on farms, but that’s enough not just to feed everyone at home but also to make the US a leading food exporter. Almost all the farm work is done by machines, which are immune to disease. Lockdowns therefore have only a small impact on farming.

Imagine a wheat field at the height of the Black Death. If you tell the farmhands to stay home at harvest time, you get starvation. If you tell the farmhands to come and harvest, they might infect one another. What to do?

Now imagine the same wheat field in 2020. A single GPS-guided combine can harvest the entire field with far greater efficiency — and with zero chance of infection. While in 1349 an average farmhand reaped about 5 bushels per day, in 2014 a combine set a record by harvesting 30,000 bushels in a day. Consequently Covid-19 had no significant impact on global production of staple crops such as wheat, maize and rice.

To feed people it is not enough to harvest grain. You also need to transport it, sometimes over thousands of kilometres. For most of history, trade was one of the main villains in the story of pandemics. Deadly pathogens moved around the world on merchant ships and long-distance caravans. For example, the Black Death hitchhiked from east Asia to the Middle East along the Silk Road, and it was Genoese merchant ships that then carried it to Europe. Trade posed such a deadly threat because every wagon needed a wagoner, dozens of sailors were required to operate even small seagoing vessels, and crowded ships and inns were hotbeds of disease.

Automation and the internet made extended lockdowns viable, at least in developed countries

In 2020, global trade could go on functioning more or less smoothly because it involved very few humans. A largely automated present-day container ship can carry more tons than the merchant fleet of an entire early modern kingdom. In 1582, the English merchant fleet had a total carrying capacity of 68,000 tons and required about 16,000 sailors. The container ship OOCL Hong Kong, christened in 2017, can carry some 200,000 tons while requiring a crew of only 22.

True, cruise ships with hundreds of tourists and aeroplanes full of passengers played a major role in the spread of Covid-19. But tourism and travel are not essential for trade. The tourists can stay at home and the business people can Zoom, while automated ghost ships and almost human-less trains keep the global economy moving. Whereas international tourism plummeted in 2020, the volume of global maritime trade declined by only 4 per cent.

Automation and digitalisation have had an even more profound impact on services. In 1918, it was unthinkable that offices, schools, courts or churches could continue functioning in lockdown. If students and teachers hunker down in their homes, how can you hold classes? Today we know the answer. The switch online has many drawbacks, not least the immense mental toll. It has also created previously unimaginable problems, such as lawyers appearing in court as cats. But the fact that it could be done at all is astounding.

In 1918, humanity inhabited only the physical world, and when the deadly flu virus swept through this world, humanity had no place to run. Today many of us inhabit two worlds — the physical and the virtual. When the coronavirus circulated through the physical world, many people shifted much of their lives to the virtual world, where the virus couldn’t follow.

Of course, humans are still physical beings, and not everything can be digitalised. The Covid year has highlighted the crucial role that many low-paid professions play in maintaining human civilisation: nurses, sanitation workers, truck drivers, cashiers, delivery people. It is often said that every civilisation is just three meals away from barbarism. In 2020, the delivery people were the thin red line holding civilisation together. They became our all-important lifelines to the physical world.

The internet holds on

As humanity automates, digitalises and shifts activities online, it exposes us to new dangers. One of the most remarkable things about the Covid year is that the internet didn’t break. If we suddenly increase the amount of traffic passing on a physical bridge, we can expect traffic jams, and perhaps even the collapse of the bridge. In 2020, schools, offices and churches shifted online almost overnight, but the internet held up.

We hardly stop to think about this, but we should. After 2020 we know that life can go on even when an entire country is in physical lockdown. Now try to imagine what happens if our digital infrastructure crashes.

Information technology has made us more resilient in the face of organic viruses, but it has also made us far more vulnerable to malware and cyber warfare. People often ask: “What’s the next Covid?” An attack on our digital infrastructure is a leading candidate. It took several months for coronavirus to spread through the world and infect millions of people. Our digital infrastructure might collapse in a single day. And whereas schools and offices could speedily shift online, how much time do you think it will take you to shift back from email to snail-mail?

What counts?

The Covid year has exposed an even more important limitation of our scientific and technological power. Science cannot replace politics. When we come to decide on policy, we have to take into account many interests and values, and since there is no scientific way to determine which interests and values are more important, there is no scientific way to decide what we should do.

For example, when deciding whether to impose a lockdown, it is not sufficient to ask: “How many people will fall sick with Covid-19 if we don’t impose the lockdown?”. We should also ask: “How many people will experience depression if we do impose a lockdown? How many people will suffer from bad nutrition? How many will miss school or lose their job? How many will be battered or murdered by their spouses?”

Even if all our data is accurate and reliable, we should always ask: “What do we count? Who decides what to count? How do we evaluate the numbers against each other?” This is a political rather than scientific task. It is politicians who should balance the medical, economic and social considerations and come up with a comprehensive policy.

Similarly, engineers are creating new digital platforms that help us function in lockdown, and new surveillance tools that help us break the chains of infection. But digitalisation and surveillance jeopardise our privacy and open the way for the emergence of unprecedented totalitarian regimes. In 2020, mass surveillance has become both more legitimate and more common. Fighting the epidemic is important, but is it worth destroying our freedom in the process? It is the job of politicians rather than engineers to find the right balance between useful surveillance and dystopian nightmares.

Three basic rules can go a long way in protecting us from digital dictatorships, even in a time of plague. First, whenever you collect data on people — especially on what is happening inside their own bodies — this data should be used to help these people rather than to manipulate, control or harm them. My personal physician knows many extremely private things about me. I am OK with it, because I trust my physician to use this data for my benefit. My physician shouldn’t sell this data to any corporation or political party. It should be the same with any kind of “pandemic surveillance authority” we might establish.

Second, surveillance must always go both ways. If surveillance goes only from top to bottom, this is the high road to dictatorship. So whenever you increase surveillance of individuals, you should simultaneously increase surveillance of the government and big corporations too. For example, in the present crisis governments are distributing enormous amounts of money. The process of allocating funds should be made more transparent. As a citizen, I want to easily see who gets what, and who decided where the money goes. I want to make sure that the money goes to businesses that really need it rather than to a big corporation whose owners are friends with a minister. If the government says it is too complicated to establish such a monitoring system in the midst of a pandemic, don’t believe it. If it is not too complicated to start monitoring what you do — it is not too complicated to start monitoring what the government does.

Third, never allow too much data to be concentrated in any one place. Not during the epidemic, and not when it is over. A data monopoly is a recipe for dictatorship. So if we collect biometric data on people to stop the pandemic, this should be done by an independent health authority rather than by the police. And the resulting data should be kept separate from other data silos of government ministries and big corporations. Sure, it will create redundancies and inefficiencies. But inefficiency is a feature, not a bug. You want to prevent the rise of digital dictatorship? Keep things at least a bit inefficient.

Over to the politicians

The unprecedented scientific and technological successes of 2020 didn’t solve the Covid-19 crisis. They turned the epidemic from a natural calamity into a political dilemma. When the Black Death killed millions, nobody expected much from the kings and emperors. About a third of all English people died during the first wave of the Black Death, but this did not cause King Edward III of England to lose his throne. It was clearly beyond the power of rulers to stop the epidemic, so nobody blamed them for failure.

But today humankind has the scientific tools to stop Covid-19. Several countries, from Vietnam to Australia, proved that even without a vaccine, the available tools can halt the epidemic. These tools, however, have a high economic and social price. We can beat the virus — but we aren’t sure we are willing to pay the cost of victory. That’s why the scientific achievements have placed an enormous responsibility on the shoulders of politicians.

It is the job of politicians rather than engineers to find the right balance between useful surveillance and dystopian nightmares

Unfortunately, too many politicians have failed to live up to this responsibility. For example, the populist presidents of the US and Brazil played down the danger, refused to heed experts and peddled conspiracy theories instead. They didn’t come up with a sound federal plan of action and sabotaged attempts by state and municipal authorities to halt the epidemic. The negligence and irresponsibility of the Trump and Bolsonaro administrations have resulted in hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.

In the UK, the government seems initially to have been more preoccupied with Brexit than with Covid-19. For all its isolationist policies, the Johnson administration failed to isolate Britain from the one thing that really mattered: the virus. My home country of Israel has also suffered from political mismanagement. As is the case with Taiwan, New Zealand and Cyprus, Israel is in effect an “island country”, with closed borders and only one main entry gate — Ben Gurion Airport. However, at the height of the pandemic the Netanyahu government has allowed travellers to pass through the airport without quarantine or even proper screening and has neglected to enforce its own lockdown policies.

Both Israel and the UK have subsequently been in the forefront of rolling out the vaccines, but their early misjudgments cost them dearly. In Britain, the pandemic has claimed the lives of 120,000 people, placing it sixth in the world in average mortality rates. Meanwhile, Israel has the seventh highest average confirmed case rate, and to counter the disaster it resorted to a “vaccines for data” deal with the American corporation Pfizer. Pfizer agreed to provide Israel with enough vaccines for the entire population, in exchange for huge amounts of valuable data, raising concerns about privacy and data monopoly, and demonstrating that citizens’ data is now one of the most valuable state assets.

While some countries performed much better, humanity as a whole has so far failed to contain the pandemic, or to devise a global plan to defeat the virus. The early months of 2020 were like watching an accident in slow motion. Modern communication made it possible for people all over the world to see in real time the images first from Wuhan, then from Italy, then from more and more countries — but no global leadership emerged to stop the catastrophe from engulfing the world. The tools have been there, but all too often the political wisdom has been missing.

Foreigners to the rescue

One reason for the gap between scientific success and political failure is that scientists co-operated globally, whereas politicians tended to feud. Working under much stress and uncertainty, scientists throughout the world freely shared information and relied on the findings and insights of one another. Many important research projects were conducted by international teams. For example, one key study that demonstrated the efficacy of lockdown measures was conducted jointly by researchers from nine institutions — one in the UK, three in China, and five in the US.

In contrast, politicians have failed to form an international alliance against the virus and to agree on a global plan. The world’s two leading superpowers, the US and China, have accused each other of withholding vital information, of disseminating disinformation and conspiracy theories, and even of deliberately spreading the virus. Numerous other countries have apparently falsified or withheld data about the progress of the pandemic.

The lack of global co-operation manifests itself not just in these information wars, but even more so in conflicts over scarce medical equipment. While there have been many instances of collaboration and generosity, no serious attempt was made to pool all the available resources, streamline global production and ensure equitable distribution of supplies. In particular, “vaccine nationalism” creates a new kind of global inequality between countries that are able to vaccinate their population and countries that aren’t.

It is sad to see that many fail to understand a simple fact about this pandemic: as long as the virus continues to spread anywhere, no country can feel truly safe. Suppose Israel or the UK succeeds in eradicating the virus within its own borders, but the virus continues to spread among hundreds of millions of people in India, Brazil or South Africa. A new mutation in some remote Brazilian town might make the vaccine ineffective, and result in a new wave of infection.

In the present emergency, appeals to mere altruism will probably not override national interests. However, in the present emergency, global co-operation isn’t altruism. It is essential for ensuring the national interest.

Anti-virus for the world

Arguments about what happened in 2020 will reverberate for many years. But people of all political camps should agree on at least three main lessons.

First, we need to safeguard our digital infrastructure. It has been our salvation during this pandemic, but it could soon be the source of an even worse disaster.

Second, each country should invest more in its public health system. This seems self-evident, but politicians and voters sometimes succeed in ignoring the most obvious lesson.

Third, we should establish a powerful global system to monitor and prevent pandemics. In the age-old war between humans and pathogens, the frontline passes through the body of each and every human being. If this line is breached anywhere on the planet, it puts all of us in danger. Even the richest people in the most developed countries have a personal interest to protect the poorest people in the least developed countries. If a new virus jumps from a bat to a human in a poor village in some remote jungle, within a few days that virus can take a walk down Wall Street.

The skeleton of such a global anti-plague system already exists in the shape of the World Health Organization and several other institutions. But the budgets supporting this system are meagre, and it has almost no political teeth. We need to give this system some political clout and a lot more money, so that it won’t be entirely dependent on the whims of self-serving politicians. As noted earlier, I don’t believe that unelected experts should be tasked with making crucial policy decisions. That should remain the preserve of politicians. But some kind of independent global health authority would be the ideal platform for compiling medical data, monitoring potential hazards, raising alarms and directing research and development.

Many people fear that Covid-19 marks the beginning of a wave of new pandemics. But if the above lessons are implemented, the shock of Covid-19 might actually result in pandemics becoming less common. Humankind cannot prevent the appearance of new pathogens. This is a natural evolutionary process that has been going on for billions of years, and will continue in the future too. But today humankind does have the knowledge and tools necessary to prevent a new pathogen from spreading and becoming a pandemic.

If Covid-19 nevertheless continues to spread in 2021 and kill millions, or if an even more deadly pandemic hits humankind in 2030, this will be neither an uncontrollable natural calamity nor a punishment from God. It will be a human failure and — more precisely — a political failure.

Source: ft.com