The conversation on banning certain uses of artificial intelligence (AI) is back on the legislative agenda. The European Commission’s public consultation closed recently, leaving the EU to grapple with what the public think about AI regulation, write Nani Jansen Reventlow and Sarah Chander.

Nani Jansen Reventlow is Director of the Digital Freedom Fund, working on strategic litigation to defend human rights in the digital environment. Sarah Chander is Senior Policy Adviser at European Digital Rights (EDRi), a network of 44 digital rights organisations in Europe.

Last week’s announcements from tech giants IBM, Amazon and Microsoft – that they would partially or temporarily ban the use of facial recognition by law enforcement – were framed in the language of racial justice (in the case of IBM) and human rights (in the case of Microsoft).

The bans follow years of tireless campaigning by racial justice and human rights activists, and is a testament to the power of social movements. In the context of artificial intelligence more generally, human rights organisations are also making clear demands about upholding human rights, protecting marginalised communities, and, therefore, banning certain uses of AI. Will European policymakers follow the lead of big tech and heed these demands?

To ‘fix’ or to ban?

So far, the EU policy debate has only partially addressed the harms resulting from AI. Industry has ensured that the words innovation, investment and profit ring loudly and consistently.

What we are left with is described by some as ‘ethics-washing‘; a discourse of ‘trustworthy’ or ‘responsible’ AI, without clarity about how people and human rights will be protected by law. Addressing AI’s impact on marginalised groups is primarily spoken of as the need to ‘fix bias’ through system tweaks, better data and more diverse design teams.

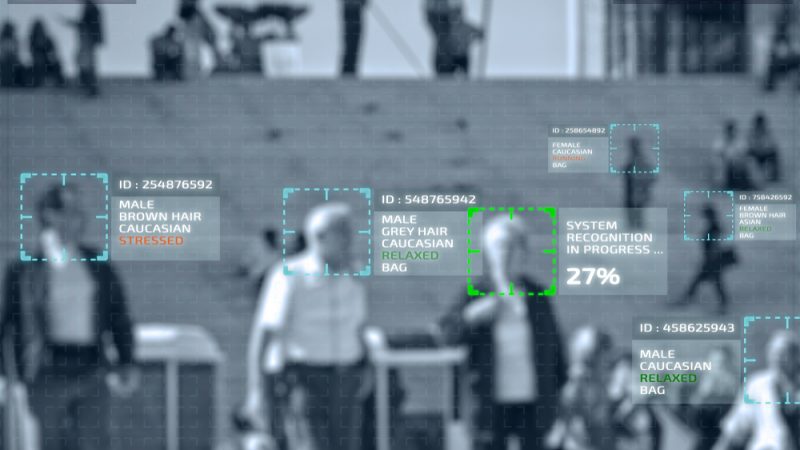

But bias is a ‘captivating diversion.’ The focus on ‘fixing’ bias has swayed the regulatory conversation in favour of technical fixes to AI, rather than looking at how its deployment changes governance of public sector functions and essential services, leads to mass surveillance, and exacerbates racialised over-policing.

Focusing on ‘bias’ locates AI’s problems with flawed individuals who embed their prejudices into the systems they build. Whilst bias is real, this framing lends itself to the dangerous argument that deep, structural inequalities can simply be ‘fixed’. This is a red herring and skips a necessary first step: a democratic conversation about the uses of AI we find acceptable and the ones we don’t. If we don’t debate this, we allow a profit-motivated industry to decide the answer.

Instead, we need to proactively define limits for the use of AI. Truly protecting people and prioritising human rights requires a focus on what is termed by the Algorithmic Justice League as “impermissible use.” They argue that “justice requires that we prevent AI from being used by those with power to increase their absolute level of control, particularly where it would automate long-standing patterns of injustice.” European policymakers need to help set those boundaries.

Where do we draw the (red) line?

AI is being designed, deployed and promoted for myriad functions touching almost all areas of our lives. In policing, migration control, and social security the harms are becoming evident, and sometimes the deployment of AI will literally be a matter of life and death. In other areas, automated systems will make life-altering decisions determining the frequency of interactions with police, the allocation of health care services, whether we can access social benefits, whether we will be hired for a new job, or whether or not our visa application will be approved.

Thanks to the work of organizers and researchers, the discriminatory impact of AI in policing is now part of the political conversation, but AI has the potential to harm many other groups and communities in ways still largely obscured by the dominant narrative of AI’s productive potential.

Many organisations are now asking, if a system has the potential to produce serious harm, why would we allow it? If a system is likely to structurally disadvantage marginalised groups, do we want it?

For example, European Digital Rights (EDRi) are calling to ban uses of AI which are incompatible with human rights, in predictive policing, at the border, facial recognition and indiscriminate biometric processing in public places. The European Disability Forum echoes the call for a ban on biometric identification systems, warning that sensitive data about an individual’s chronic illness or disability could be used to discriminate them.

Meanwhile, pro-industry groups characterise increased oversight and precautionary principles as a “drag on innovation and adoption of technology.” Policymakers should not buy in to this distraction. We cannot shy away from discussing the need for legal limits for AI and bans on impermissible uses which clearly violate human rights.

Yet this is only a first step—the beginning of a conversation. This conversation needs to be people-centered; the perspectives of individuals and communities whose rights are most likely to be violated by AI are needed to make sure the red lines around AI are drawn in the right places.

Source: euractiv.com